Lasting Happiness in a Changing World

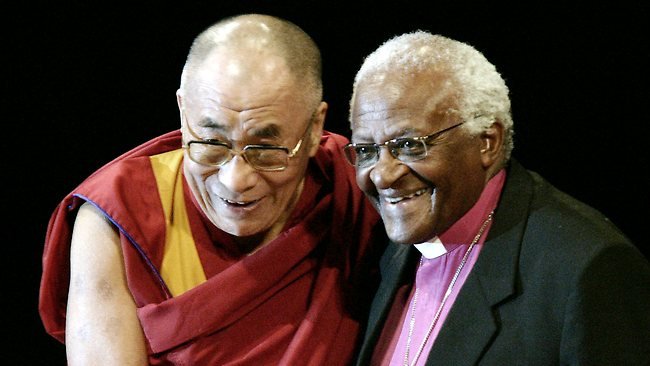

This deep and delightful book, published in 2017, became an immediate best-seller worldwide. The wisdom of these two great men in their eighties is surprisingly fresh and practical, and relevant for all of us in handling daily stress and raising our wellbeing.

Douglas Abrams, who compiled the book, shows how modern research offers similar pointers for human happiness to the Buddhist and Christian teachings this book explores. This book offers a lot of useful insights from all three sources, illustrated by many vivid recollections from the dramatic lives these two men have led.

For example, the Dalai Lama says “a compassionate concern for others’ well-being is the source of happiness” and Archbishop Tutu speaks of the similar African concept of Ubuntu, often defined as ‘I am what I am because of who we all are’. The book then cites an American neuroscientist, Richard Davidson, who also affirms that generosity towards others is essential for lasting wellbeing.

Four brain circuits for wellbeing

More specifically, Davidson’s research shows that there are four independent brain circuits that influence our lasting well-being. The first is “our ability to maintain positive states.” These two great spiritual leaders are saying that the fastest way to this state is to start with love and compassion. The second circuit is responsible for “our ability to recover from negative states.” What is fascinating is these circuits are totally independent. One could be good at maintaining positive states but easily fall into an abyss of a negative state from which one had a hard time recovering. That explained a lot in my life.

The third circuit, also independent but essential to the others, is “our ability to focus and avoid mind-wandering.” This of course was the circuit that so much of meditation exists to develop. Whether it was focusing on one’s breath, or a mantra, or the analytic meditation that the Dalai Lama does each morning, this ability to focus one’s attention is crucial.

The fourth and final circuit is “our ability to be generous.” It is no wonder that our brains feel so good when we help others or are helped by others, or even witness others being helped. There is strong and compelling research that we come factory equipped for cooperation, compassion, and generosity.

Sadly, our empathy does not seem to extend to those who are outside our “group” which is perhaps why the Archbishop and the Dalai Lama are constantly reminding us that we are, in fact, one group – humanity. The ability and desire to cooperate and to be generous to others is there in our neural circuits, and it can be harnessed personally, socially, and globally.

Both men come across as warm, humble characters with huge compassion and wisdom, who never pontificate, and have a lot of useful insights to share. The Dalai Lama frequently emphasises, “we are all same human beings,” and admits that he only gets stressed in his public life when he thinks he’s different.

The mental immune system

Another fascinating idea in this book is the Dalai Lama’s belief that we have a mental immune system which we can nourish just like the physical immune system. Here’s how he explains it in the book:

“Think about it this way. If your health is strong, when viruses come they will not make you sick. If your overall health is weak, even small viruses will be very dangerous for you. Similarly, if your mental health is sound, then the disturbances come, you will have some distress but recover quicker. If your mental health is not good, then small disturbances, small problems will cause you much pain and suffering. You will have much fear and worry, much sadness and despair, much anger and aggravation.

“People would like to be able to take a pill that makes their fear and anxiety go away and makes them immediately feel peaceful. This is impossible. One must develop the mind over time and cultivate mental immunity.

“One time I was talking to Al Gore, the American vice president. He said that he had lots of problems, lots of difficulties that were causing him a great deal of anxiety. I said to him that we human beings have the ability to make a distinction between the rational level and the emotional level. At the rational level, we accept that this is a serious problem that we have to deal with, but at the deeper, emotional level, we are able to keep calm. Like the ocean has many waves on the surface but deep down it is quite calm. This is possible if we know how to develop mental immunity.”

An interesting feature of this book is that it is structured around questions which the public wanted to ask of these two wise teachers. And the most popular question was how to handle the pain and suffering in the world. You might think they’ve learned to rise above it, but their first response is that we need to stay connected and feel this pain.

Desmond Tutu comments on the value of action, however small: “start where you are and do what you can where you are. And yes, be appalled…That’s part of the greatness of who we are – that you are distressed about someone who is not family in any conventional way.”

Desmond Tutu describes how we can grow through hardship, using vivid examples from his own life and Nelson Mandela’s during the long struggle to end apartheid. He says “it is the hard times that knit us more closely together.”

A Buddhist View of Friendship

One of my favourite concepts in Buddhism is metta: this word is usually translated as loving-kindness, but its root meaning is the nature of a friend. As frictions grow in life, we need to find more kindness and tolerance for everyone we meet. What’s different in friendship is the chance to practice metta more deeply, and learn from our oversights. I recently noticed I was getting irritable with friends over minor mistakes. When I looked at this, I realised that I need to show more kindness to them – and to myself. It was my perfectionist expectations of myself and others that needed to be released, with kindness.

Tibetan Monks, image courtesy of Tibet Vista

Metta is a very nourishing quality, and when we show it to others, we’re also nourishing ourselves. This is a classic case of treating others as you would like to be treated yourself. Modern life expects us to be so up-together all the time: one blessing of friendships is that you should feel safe to show your failings, admit them, and still feel valued.

Another Buddhist teaching about friendship is the way a true friend is constant in good times or bad. It’s part of the wider Buddhist belief in a non-attachment to material circumstances. This is all a useful reminder of what resilience can mean for us.

A large part of The Book of Joy addresses obstacles to joy, and another major section explores the Eight Pillars of Joy, such as humour, forgiveness and gratitude. The last part is Joy Practices: guided meditations, prayers, breathing practices, and other valuable methods to make all this a reality in daily life. The Book of Joy fully deserves its best-seller status: it’s a charming manual for deeper wellbeing.